A Year Since Baghuz, the Islamic State Is Neither Defeated nor Resurging (Yet)

Original Article by Washington Institute for Near East Policy, on March 25, 2020

Although attack statistics have declined, the continued lack of stable governance in Diyala and Deir al-Zour shows that Washington and its partners have not absorbed the lessons provided by previous insurgencies.

A lot has happened for the Islamic State since it lost its last sliver of territory in Baghuz, Syria, a year ago this week. Most notable was the death of its first self-declared caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who was killed in a U.S. Special Forces raid in Barisha, Syria, last October. IS subsequently announced his successor as Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Quraishi, and thus far, there have been no signs of any disruption in its activities as a result of this transition. Indeed, despite the U.S. government’s boisterous pronouncements that IS was defeated after the fall of Baghuz, the organization remains active.

Yet it is also too early to state that IS has rebounded. Rather, it is surviving and waiting for the right moments to take advantage—and not necessarily in the same manner it did in 2004-2006 (when it first became relevant) or 2012-2014 (when it resurfaced after major defeats in Iraq). Even so, many of the underlying sectarian and governance dynamics that led to its reemergence eight years ago persist in both Iraq and Syria.

CONTINUED ALLEGIANCE

In the aftermath of last year’s territorial losses, IS launched a video campaign titled “And the [Best] Outcome Is for the Righteous,” aiming to reaffirm pledges of allegiance to Baghdadi among various affiliates within its global network. The campaign garnered support from the core branches in Iraq and Syria as well as outlying “provinces” and supporters in Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Chechnya, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Libya, Mozambique, Nigeria, the Philippines, Somalia, Tunisia, Turkey, and Yemen.

IS launched a similar photo essay campaign after Baghdadi’s death, showing affiliates in various countries pledging baya (religious oath of allegiance) to the new leader. This time they included branches in Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, the Congo, Egypt, Indonesia, Iraq, Libya, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, Somalia, Syria, Tunisia, and Yemen.

OPERATIONS SINCE BAGHUZ

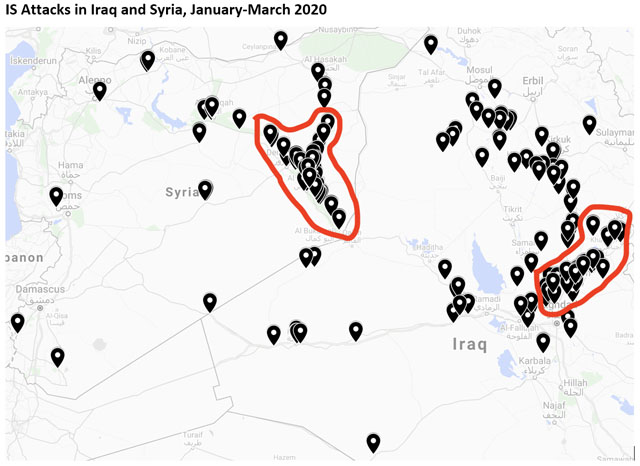

From the fall of Baghuz through March 19, 2020, IS claimed responsibility for more than 2,000 attacks in Iraq and Syria combined. In Syria, it claimed 973 attacks in the following governorates:

- 580 in Deir al-Zour

- 150 in Raqqa

- 141 in Hasaka

- 48 in Homs

- 33 in Deraa

- 16 in Aleppo

- 4 in Damascus

- 1 in Quneitra

In Iraq, it claimed 1,143 attacks in the following governorates:

- 452 in Diyala

- 171 in Kirkuk

- 146 in Baghdad

- 138 in Nineveh

- 133 in Anbar

- 71 in Salah al-Din

- 32 in Babil

From this data, one can see that IS has a much stronger base in the Deir al-Zour region of Syria and the Diyala region of Iraq than anywhere else. It also suggests that smaller cells are still relatively active in the Kirkuk, Raqqa, Baghdad, Hasaka, Nineveh, and Anbar regions, conducting around 11-15 attacks per month. The IS command-and-control infrastructure thus appears intact.

Although the attack numbers seem impressive at first glance, they are actually low from a comparative perspective (albeit disturbingly widespread). In Iraq, for instance, 2019 witnessed the lowest level of civilian deaths since the 2003 war, and that downward trend has seemingly continued this year. According to Iraq Body Count, 261 civilians have been killed there through February, which amounts to a total of 1,566 if one extrapolates the numbers for the rest of the year. That is far less than in past years: for example, Iraq suffered:

- 2,392 deaths in 2019

- 3,319 in 2018

- 13,183 in 2017

- 20,218 in 2014

- 29,526 in the peak year of 2006

Of course, the Islamic State is not responsible for all of these deaths, but it has been the predominant insurgent faction operating in Iraq since at least 2009.

The data might also indicate that the actual number of IS fighters remaining in Iraq is much lower than commonly estimated, since the level of violence there is well below even the group’s weakest point: namely, between 2009 and 2011, following the tribal “awakening” and U.S. troop surge, when annual deaths hovered around 4,000-5,000. Over the past year, the U.S. government, the UN, and other parties have asserted that there are as many as 25,000 fighters left in Iraq and Syria combined: around 11,000 in Iraq and 14,000 in Syria. If those numbers were accurate, however, the violence would likely have been much worse over the past year than the death statistics indicate. (If, however, U.S./UN estimates include IS members involved in non-military activities, then comparisons with past periods of resurgence cannot be made using these metrics, since IS did not have such a broad bureaucratic apparatus until 2013.)

LOOKING FORWARD

Diyala’s continued status as the epicenter of IS attacks in Iraq is unsurprising given its longstanding role as a key locale for the organization, whether as a staging ground during its budding insurgency in 2003-2004 or as a fallback following its defeats from 2007 to 2009. Part of this is due to terrain; the area is studded with mountains, canals, groves, and other features that make hiding out and ambushes easier and conducting effective counter-operations more difficult. In addition to continued killings, Diyala has suffered a number of kidnappings in 2020—likely the group’s way of obtaining ransom money, as it did in Mosul between 2009 and 2014 when it was attempting to stabilize and return.

Diyala is also at the intersection of various ethnic and religious fault lines between Sunni Arabs, Shia Arabs, Kurds, and Turkmens. IS can play off of these divisions to find rich targeting opportunities, especially since the Badr Organization—an Iranian-backed Shia group that is part of Iraq’s al-Hashd al-Shaabi militia network—currently controls the area. These same dynamics make it difficult for U.S. Special Forces to operate in Diyala. At the same time, the area’s mixed composition has limited the Islamic State’s ability to take full control there itself, including in its most recent iteration.

To truly suppress IS activity in this hotspot, Washington should keep reminding Baghdad that its current course—enabling Iranian proxies to establish local control—will only feed the next IS insurgency. Iraq’s recent history has proven that ceding ground to sectarian forces perpetuates a never-ending boom-and-bust-cycle for the jihadist movement.

Although the spread of violence over a broader swath of Iraqi territory is disconcerting, the next IS breakout would likely be centered in Syria, around towns on the east side of the Euphrates River. The simmering discontent in the Deir al-Zour region gives the group its greatest platform for retaking territory. Of all the areas that lie within the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), Deir al-Zour is under the least direct control by the administration’s military arm, the Syrian Democratic Forces—especially since the partial U.S. military withdrawal and Turkish invasion last October. As a result, SDF and coalition raids against IS targets in the area are down from 32 in early 2019 to 16 in early 2020, according to the Rojava Information Center. Furthermore, the prevailing circumstances have limited humanitarian assistance and prevented any attempt to begin local rehabilitation and reconstruction efforts. Meanwhile, news outlet Deirezzor 24 reported that IS attempted to reimpose taxes on the local population in February, with noted cases in the towns of al-Hawayij and al-Rugheib.

The group’s high level of activity in Deir al-Zour is also due to the fact that the population in the east is mainly Arab, and located far from the central authorities of the Kurdish-led AANES further north. In this sense, the coalition missed its opportunity to establish a sustainable governance structure in the area. Moreover, local tribes span both sides of the Euphrates, giving nearby forces from the Assad regime, Iran, and Shia militia proxies ample room to stoke tensions and divisions among the Sunni Arab majority.

In light of these circumstances, the coalition should reach out to local councils in the Deir al-Zour region of the AANES, with the aim of strengthening ties and restricting the Islamic State’s freedom of movement and ability to remain active in the area. This could also hinder the group from attempting another “breaking the walls” campaign. In that scenario, IS could free thousands of its fighters in local prisons and tens of thousands of supporters in refugee camps dotting the northeast, thereby replenishing both its military ranks and its state-building project. Such attempts occurred from within various jails and camps last October following the Turkish invasion, and more recently in mid-March, when IS prisoners attempted a breakout in the Ghweiran neighborhood of Hasaka. Maintaining local stability would also create a firewall against the Assad regime and its allies attempting to retake this region, which would only cause more suffering for residents and spark further IS recruitment.

As for the growing coronavirus epidemic in the Middle East, it is too early to predict how (and how much) it might affect local dynamics and IS in particular. At the very least, however, it will likely hinder international and local action against the group due to changing priorities. IS noted this likelihood in its al-Naba newsletter a week ago, arguing that its supporters should not show any pity against their enemies, but in fact pressure them in any way possible at home and abroad.

Therefore, while the Islamic State is not “back,” or even nearly as strong as it was from 2014 to 2016, the anniversary of its 2019 territorial defeat is still a grim one. The lessons from coalition failures following the awakening and surge campaigns in Iraq have yet to be heeded, and the window of opportunity to address the political roots of future IS insurgencies may already have closed again.

Aaron Zelin is the Richard Borow Fellow at The Washington Institute and author of the new book Your Sons Are at Your Service: Tunisia’s Missionaries of Jihad.